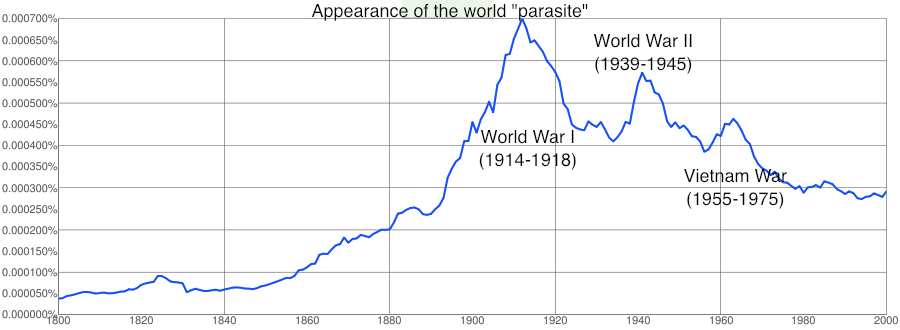

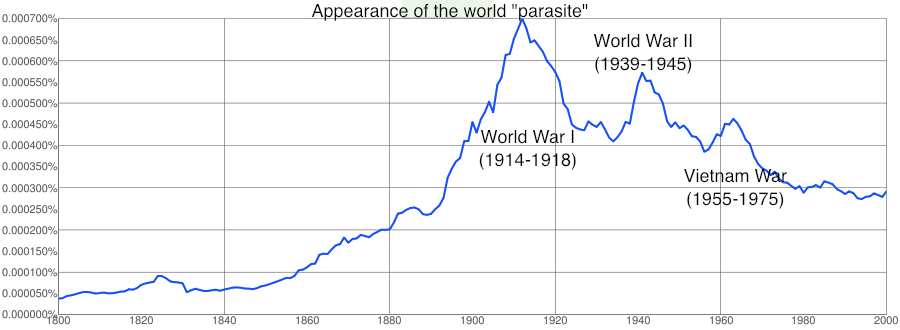

Zach and I were playing around with Google’s Ngram Viewer recently. To learn more about the program you should check out the link, but in a nutshell we were using the program to track the frequency of particular words in the english language as a function of how frequently they occur in books. I, of course, decided to examine changes in how frequently the word “parasite” was used. Here is what I found:

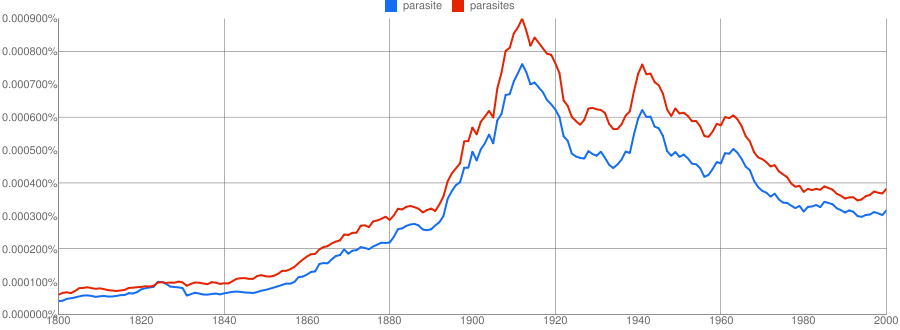

This chart shows what percent of words printed in books written in english were the word “parasite” or “parasites”. Zach immediately noted that peaks on the graph corresponded to times of war. Check it out (as both lines follow the same trend I removed “parasites” to create additional space):

The field of parasitology receives regular boosts during times of war. By “boosts,” I mean increased hiring of parasitologists and increased funding available for parasitological studies. When soldiers from the USA and England travel the world in times of war, they encounter lots of nasty, debilitating parasites which are not a problem back home. These parasites freak out soldiers, who aren’t accustomed to finding blood in their urine (from

Schistosoma haematobium infection) or unexplainable open sores (or

leishmaniasis). Additionally, these parasites make our troops less effective.

Malaria, in particular, was a major problem during wartime. This parasite is spread by mosquitos and infects red blood cells. The parasites synchronize their reproduction, and break out of old red blood cells in search of new cells at the same time. The timing depends on the parasite species, but it’s common to experience major fevers, shivering, vomiting, and anemia every two days or so when the parasites lyse their old red blood cell homes. The disease is debilitating, energetically expensive, and efficient at sending soldiers to the hospital.

–

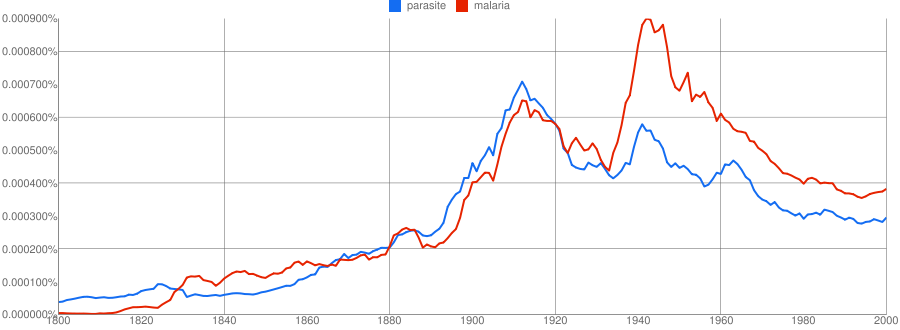

In fact, this disease kept so many soldiers off the field during World War II that major funding went into controlling the disease (

article here), leading to the production of vaccinations, medications, and mosquito control techniques. War time is a bad time to be a soldier, but a good time to be a parasitologist. In fact, you can see that our efforts to battle malaria during WWII were somewhat effective because you don’t see a prominent peak in the word “malaria” during the Vietnam War:

Please see the comments section for some really interesting suggestions provided by readers!

The peak between 1900 and 1920 (around 1914) could be from the work William Gorgas (roll tide…) was doing during the construction of the Panama Canal to eradicate malaria and yellow fever.

The word “parasite” may also be used in other contexts, especially in times of war.

For example, protesters against the Vietnam War may have been called that. The Nazis called Jews “parasites”. Has Zack just gotten more atractive to you?

The “parasite” curve peaks in 1912 and declines throughout WWI, so I don’t buy that explanation.

The ‘hump’ at 1880 may coincide with the French attempt to build the Panama Canal – its estimated 20 000-22 000 workers died during construction between 1881 and 1889, many from Malaria.

The minor blip in the 1980s could be from a host of things, it was a busy time. US and UK forces were involved in actions all over the would: Lebanon, Afghanistan, Grenada, and Falkland Islands. This doesn’t even include all the clandestine operations going on through Latin America and Africa. The 80s were a pretty turbulent time in terms of the Cold War. I’m sure all of these places had their own biological horrors to deal with.

For the earliest blip, 1830s, I would guess that would be from the various colonial efforts by the British in India and China. This has been an interesting topic to look into.

This is a very specific example, but during the Battle of Leyte Island in 1944, Allied troops started coming down with severe fevers. The Medical Corps found that the troops were being infected by schistosomiasis japonica, a blood fluke whose life cycle consisted of eggs in the feces of infected creatures, the eggs are hatched and the free swimming larva, called miracidia, then infect snails of the genus Oncomelania, where they reproduce asexually. The result of this reproduction are larva called cercaria, which shed from the snail and them must infect a suitable vertebrate host, where they then start laying eggs in the host’s intestines. (footnote 1)

Because of the high rate of infection(see footnote 2), the damaging symptoms of the disease (footnote 3), and the lack of a known cure (footnote 4), one of the US Medical Officers, Lt Col Billings, collected a vast number of infected snails, and was airlifted back to the US so that experiments could be performed to determine the life cycle of the parasite and cures for its infection (footnote 4).

Considering that most of the papers on schistosomiasis japonica are either written by Billings or cite him as a primary source, I’d say that the study of that particular parasite got a massive boost do solely to the fact that there was A) a war going on, and B) a doctor during that war didn’t really want to be shot at that much.

1. This one is wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schistosomiasis_japonica

2. “The attack rate for the battalion was 19.6 percent (102 cases as of 31 May 1945) which may be compared with an estimated XXIV Corps rate of 0.73 percent. The rates increase to 27 and 33 percent respectively as B and C companies, engaged in bridge construction, are considered separately. Moreover, the attack rate increases to the range of 41-53 percent as attention is focused on the specific platoons engaged in bridge construction. Finally as the rates are computed for the water-exposed bridge-workers themselves, these range from 71-89 percent in the various platoons of B and C Companies. Actually in dealing with the water-exposed bridge-workers it becomes a matter of trying to explain why 100 percent of them were not infected. Since a number were unfortunately not hospitalized or were not diagnosed because typical ova could not be demonstrated, the possibility of 100 percent infection in this group cannot be eliminated.” -http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwii/internalmedicinevoliii/chapter3.htm

3. see pages 98-111 of attached link – http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwii/internalmedicinevoliii/chapter3.htm

4. “Onward the 118th sailed, to the flat, watery island of Leyte. But what nobody had realized was that Leyte was also home to a nasty parasite, a liver fluke with a complicated life cycle involving snails, called a schistosome. Anyone who walked in fresh water was at risk, and there was no cure.

That deadly parasite, however, turned out to be Billings’ ticket home. Talking one day to the base surgeon, he asked if the U.S. Public Health department had any infected snails with which it could infect other animals and find out how to treat schistosomiasis. No, said the surgeon, but this was certainly an urgent need.

“If I can find some infected snails, will you send me home?” Billings asked immediately.

“Same day,” responded the surgeon.

So it was that Josh Billings and a Filipino medical officer, rubber-booted and -gloved, gathered several hundred infected snails, put them in a fruit jar, and packed them in a big box with wet blotting paper and ice. Billings received an “A” air priority status, telegraphed Ann to meet him at his mother’s apartment in Baltimore, and was in Washington 36 hours later. ” -http://esgweb1.nts.jhu.edu/hmn/F06/annals.cfm